JANE BRUCKER

BY JEANNE WILLETTE, Ph.D.

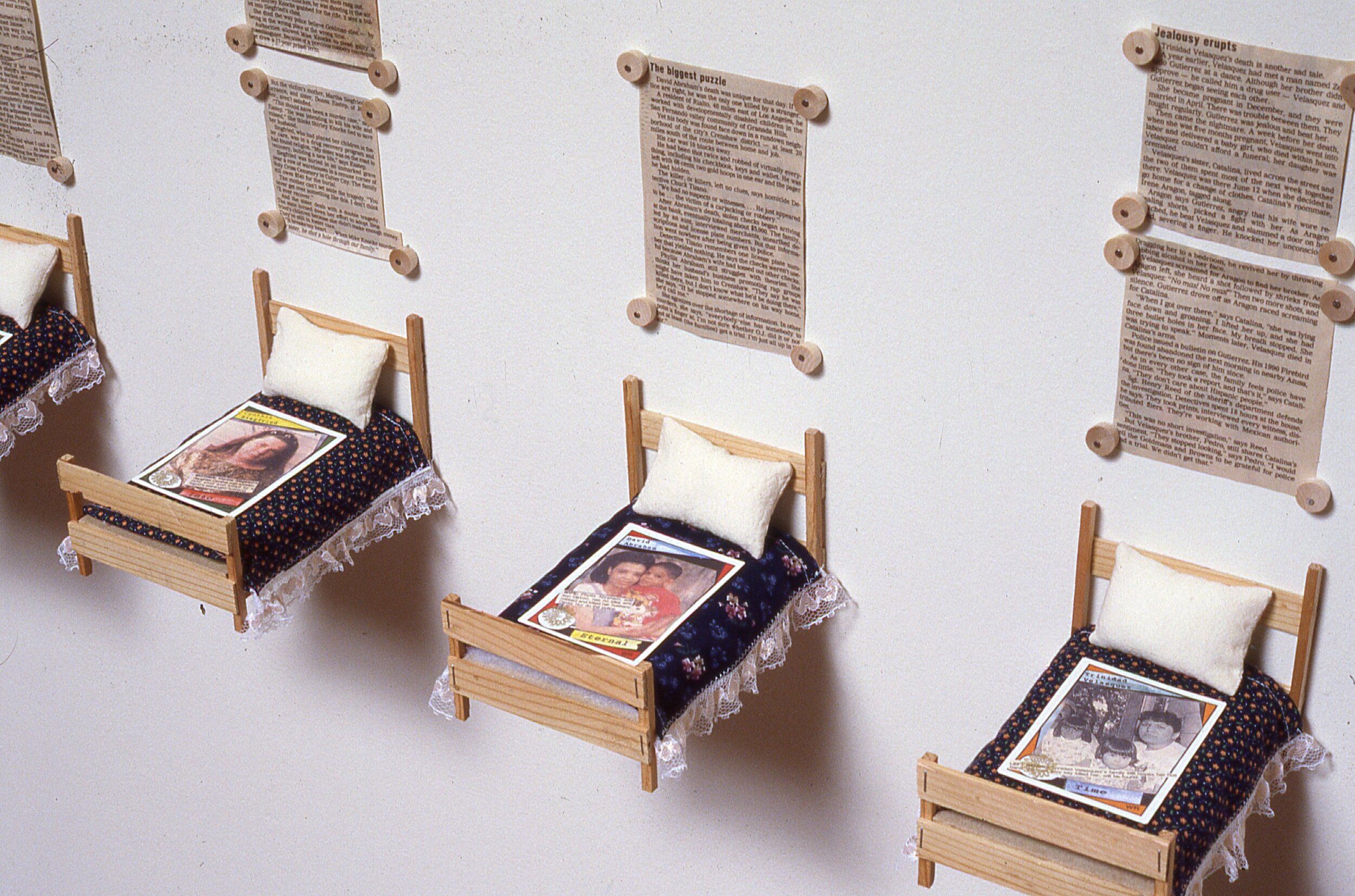

Journey-Past-Memory-Into-Eternal-Time detail (photo by Robert Wedemeyer)

As any Raymond Chandler fan knows, Los Angeles has a reputation for exotic crimes among the rich and famous. Few crimes, however, have captured the public imagination with the intensity of the double murders-still unsolved-of Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend, Ronald Goldman. For over a year the entire world watched the unfolding events with unflagging fascination, from the first arrest of the former sports hero O.J. Simpson to the day of his acquittal after the “Trial of the Century.” The story is still in progress as the now-freed O.J. lives in quiet seclusion, evicted from his country clubs, shunned by former associates, fired from his professional commitments, and unwelcome in his own Brentwood neighborhood. According to the comic strip Doonesbury, he goes from house to house searching for the murderer of his former wife, and news reports portray a man who has become a pariah in the community that once celebrated his charm and winning ways. The winners of big court trials are, as always, the lawyers who will become multimillionaires. The losers are the other six now-forgotten people murdered on the same day as Ron and Nicole, and perhaps all the other victims of domestic violence who have heard a jury discount their suffering and threats to their lives. On any average day in the City of Angels five people are murdered; the death of Nicole was just one more than normal.

In her installation, Jane Brucker takes up the contradictory and unresolved issues of and around the “O.J. event.” The other four who died on the 12h of June were unknown to the media, but their deaths were equally devastating to their families and friends. Like the Simpson and Brown cases, the other murders in Los Angeles that day have gone without resolution and conviction. As a response, Brucker fabricated Journey-Past-Memory-Into-Eternal-Time so that each of the six murdered souls might rest peacefully in tiny, painstakingly built balsa wood beds carefully made up with miniature linens. The stories of their deaths are told in squares of newsprint above the beds. Each victim is thereby equally remembered by the artist.

In American culture, Nicole Brown Simpson stood for all that was conventionally glamorous and desirable in a woman. In the mind of the feminist Brucker, however, she was also a sister. As a memorial to this relationship, the artist has built a suburban-style “house of cards” to question the popular concept of “domestic bliss” that supposedly exists in these ideal homes. The gallery viewer can enter a simulacrum of Nicole’s now deserted domain by ringing a doorbell. But instead of the famous condominium on Bundy Drive, My Sister’s House of Cards is a replica of the actual home of the artist’s real-life sister, and is composed of numerous, precariously mounted, cascading football cards. In this work, Brucker points to the possible relationship between sports and domestic violence in a nation where incidences of domestic violence double on that quintessentially American holiday, Super Bowl Sunday. Somewhere inside the chaotic home can be found the “O.J. card,” picturing the hero in his athletic prime-his mouth fiercely open, shouting.

In a related video, My Dinner with O.J., a dialogue is going on, but without words. This visual conversation takes place between two pairs of hands-one black and male; one white and female-as they eat dinner together, negotiating and navigating food, condiments and truth. The only audible sounds are those that emit from a typical dinner, and were created for this work by Los Angeles sound artist, Tom Skelly. Amidst the clinking of silver on china, the lifting and lowering of glasses, and companionable handing of condiments back and forth, the diners’ conversation is unheard. The viewer is left to ponder what it would be like to dine with a fallen hero of modern life.

JEANNE WILLETTE, Ph.D. was an arts writer and wrote about Jane Brucker’s work for the travelling exhibition Thoughtworks@LA at Laband Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, 1996; Battlecreek Art Center, Battlecreek, Michigan, 1996; and Valdosta State University Art Gallery, Valdosta, Georgia, 1997.